It was certainly worth the journey, despite the parking ticket outside Liverpool Cathedral—on a Sunday! It might only take an hour from my Manchester abode to reach the heart of Liverpool to visit the Walker Art Gallery, but it brought home to me that art (and particularly the art in Liverpool) is worth the journey—and is, in its own way, a journey in itself. But more on that later.

The Walker Gallery is very impressive indeed. It takes you—free of charge—through various centuries of art history within a dozen or so large sections featuring works by many of Europe’s best-known painters: Murillo, Rubens, Rembrandt, Poussin, Gainsborough…They’re all there. Wikipedia says it contains “one of the largest art collections in England, outside London”, which seemed about right to me.

You might think that as a priest, I would have liked the religious paintings best of all. There certainly is a lot of great faith-inspired art in Liverpool—yet another reminder of how much Christianity has enriched our culture—but truth be told, it wasn’t a religious work which most caught my attention. If I had to pick one single painting in the gallery which struck me, it was John Everett Millais’ Isabella (also known as Lorenzo and Isabella).

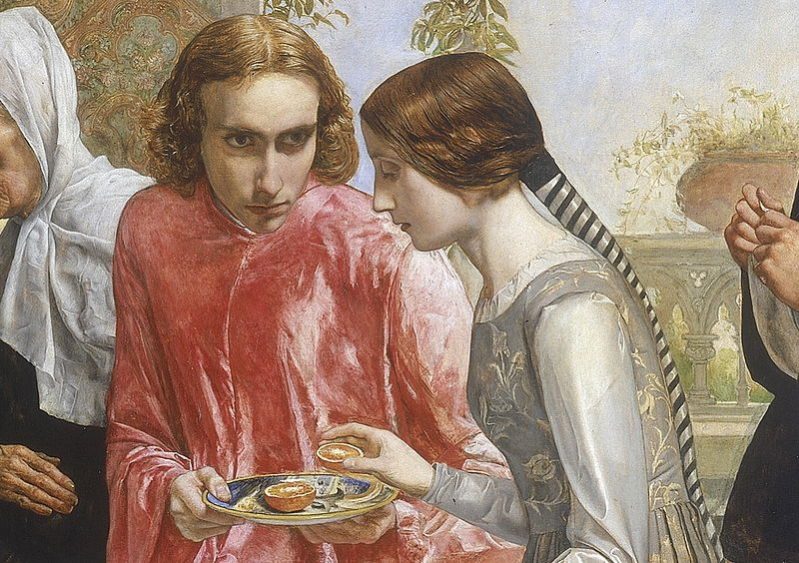

Emerging from the dull 18th-century section—an abundance of slightly tedious portraits of aristocrats and equally uninspiring landscapes (may the specialists have mercy on me!)—it was a breath of fresh air to plunge into the bright color and wild imagination of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Pride of place among them was Isabella, which is Millais’ 1849 masterpiece based on a story in Boccaccio’s Decameron and taken up later in a poem of John Keats. In the right-hand foreground (as one looks at the work) you have the two young lovers who only have eyes for each other, tragically so as this will soon lead to their undoing. The problem is that Lorenzo is only an employee and Isabella’s family, whose business is struggling, have her ear-marked for a marriage to a rich nobleman. Lorenzo will be killed by them but the rebellious Isabella will dig up his body to cut off and keep his head, burying it in a pot of basil which she then waters with her tears.

The painting shows the moment when the rest of the family seem to realize that love is in the air. I say “seem” because the artist brilliantly shows everyone doing their utmost not to let on that they have noticed. And it’s as if they have all telepathically agreed on their murderous resolve. It is extraordinary how Millais portrays their hypocritical propriety with such dramatic intensity. The elderly mother, sitting to the left of Lorenzo, does everything she can not to turn her head but is clearly aware of all that is going on. To her left, the father wipes his mouth with his napkin in an exemplary show of etiquette which only makes his ruthless intentions all the more dreadful. One brother swigs down his wine, another examines it. All have food but it hardly seems to matter to them. They are cramped together with other siblings, but in perfect order, in a way which further intensifies their ill-intentioned constraint. Only a brother in the foreground, with his splendidly muscular thigh in white stockings matching the equally white tablecloth, gives us a glimpse of the family’s real evil. The white represents their impeccable external correctness, but this same youth is leaning forward on his stool to kick the dog whose head is resting on Isabella’s lap. There is nothing white about their hearts. He appears to be concentrating on a nut-cracker as if to show his determination to crack this unfortunate liaison. The scene captures the split-second before his foot will make contact with the hound and so upset its peace and disturb the passionate encounter of the two lovers.

My friend and I left the gallery to head towards the docks. After a brief visit to the Liverpool central library, a successful combination of the best of modern and Victorian architecture full of busy youths swatting for exams, we stopped briefly in the next door museum and joined a minute of silence for the victims of the Hillsborough disaster. Outside a small crowd had gathered by a memorial and sang tunelessly but passionately “You’ll never walk alone”. As both a southerner and (for historical family reasons) an Everton fan, I was happy that I could join this tribute by authentically Scouse Liverpool supporters. A city that still gathers to remember its dead almost 30 years down the line is a city with a heart—and therefore a future.

Our journey to the docks took us past the Blessed Sacrament shine, next to a bus terminal and in the middle of a rather soulless shopping district. But there people were praying. Christ still finds His way into the heart of human journeying—and even human business.

Returning from Albert Docks (nice but somewhat commercial), we got into our car and drove to the cathedrals. The parking ticket was a wound but the Anglican temple is a majestic monument which proclaims itself to be a cathedral simply by its size and spaciousness. It’s a beautiful brown-stone building and I have to confess that, as a Catholic, I can’t help wishing it were ours! But as it’s post-Reformation by a number of centuries, I have no grounds for complaint this time.

Then to the Catholic cathedral…The crown of thorns tower is striking, the stained glass creates a powerful interior atmosphere and there is much within it that is very worthy. But the biggest disappointment was the altar-piece in the Blessed Sacrament chapel. In what should be the most beautiful chapel in the cathedral (following what we Catholics claim to believe: that Jesus Christ, God made man, is truly inside that box we call a tabernacle, under the form of bread), the painting was an abstract effort in yellow and white diagonal stripes which would mean very little to anyone. My only hope is that the forthcoming National Eucharistic Congress will inspire someone to put something better there, something, please God, with both the imagination and technical expertise of Isabella.

And this perhaps is the point I began with, and with which I end. The greatness of Millais’ work is that it tells a recognizable story and captures human feelings and passions in a discernible but imaginative manner. You know what is going on and you are brought into the scene and challenged. For this 19th-century gem is very far from being a staid re-working of what has gone before. Millais provokes and unsettles us (the work certainly did in its time). For all its daring, the artist—like other great pre-Raphaelites—shows a technical mastery which matches that of any contemporary painter of the period. It is worth going to see this work because it has taken art forward. And watching the painting, and numerous other works in the Walker Gallery (the best place for art in Liverpool), one is taken forward oneself, entering into the vision and creativity of great artists of the past to grow in both in the present. Through this experience of beauty, one deepens in one’s understanding of the human condition. It is a journey—at least a small step—out of one’s own limitations into a far greater imaginative and psychological world. If that is not traveling, I don’t know what is.

Suggested next reading: Why You Need To Ditch The Noise & Escape Into Silence ASAP