“So legendary is Lud’s Church, it is hard to find anyone who has actually been there”, writes one Peak District information website. Well, I have—in fact, a few times, the most recent of them just the other week. It’s certainly “off the beaten path”, as the site puts it, but while I wouldn’t try taking someone in a wheelchair, it’s a relatively gentle half-hour walk, uphill on country paths, from the nearest car park. Boots might not be essential but would be recommended on a wet day, particularly if you wanted to climb down the few rocks and through a muddy patch which takes you into the chasm itself.

Lud’s Church—which is anything but a church, but more on that later—is part of the Roaches escarpment in Staffordshire, in the West Midlands of England, and is geologically speaking a “chasm”. It’s a splendidly atmospheric slice into the Millstone Grit rock of the area, with sheer walls covered, to quote the site, in “algae, mosses and ferns in varying shades of vivid green, all dripping with moisture in this perfect, damp micro-climate.” If you visit it alone on a rainy day, it’s also a bit spooky with a sense of the secret sect which used to meet there in bygone days.

Secret sect! What’s all that about? Now it’s getting interesting, and maybe that’s why it’s called a church. When one goes there, one feels dissent and fear and can imagine people watching nervously at either end of the chasm while surreptitious worship took place in its depths. And that indeed is what appears to have happened.

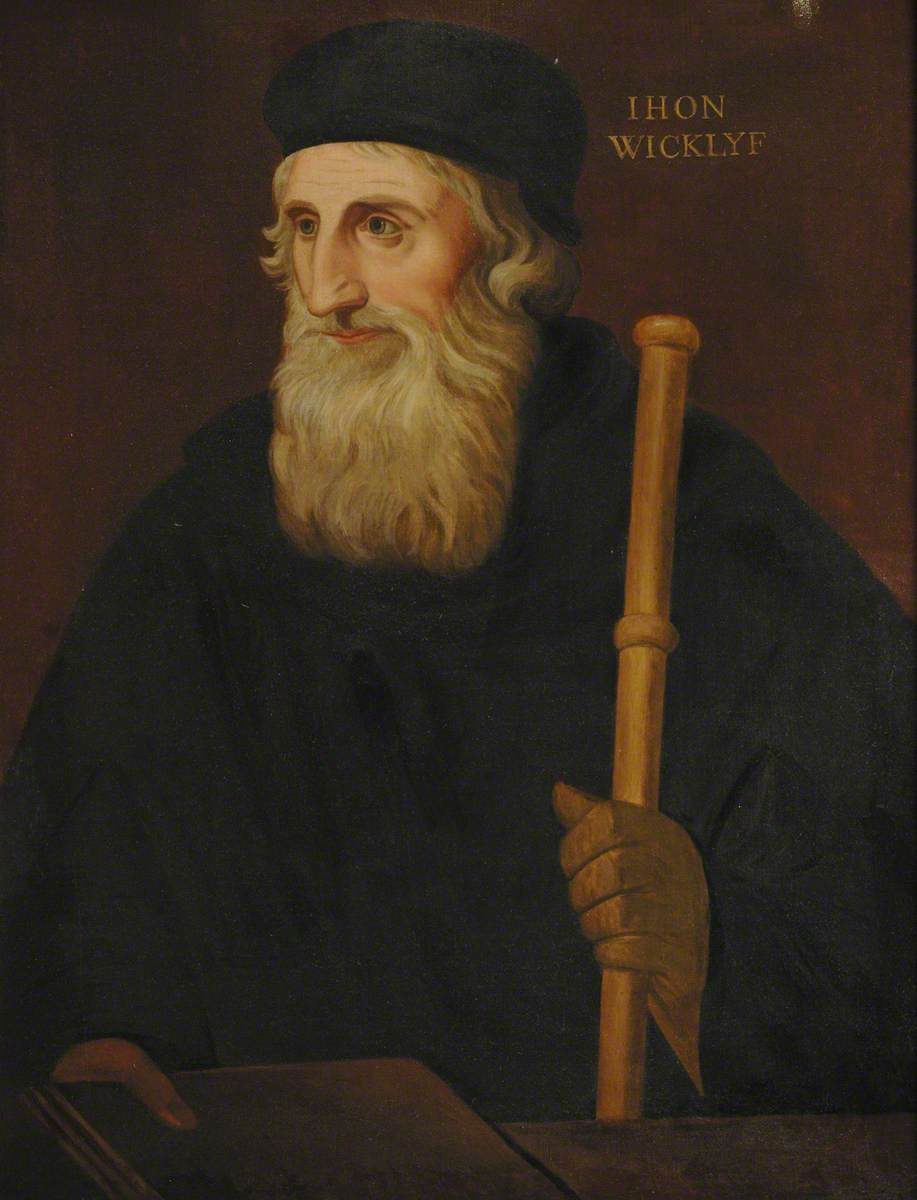

It would seem that a 15th Century heretical group known as the Lollards used to meet here for their services, led, according to some accounts, by a certain Walter de Lud-Auk (which might explain the place’s name: Lud’s Church). Followers of John Wycliffe—a Protestant avant la lettre (to put it pretentiously)—and persecuted by the authorities, the Lollards came here for their illegal gatherings. Wycliffe (ca. 1320-1384) was the driving force of a translation of the Bible into English, a revolutionary move at a time when reading Scripture in the vernacular was not encouraged. He also criticised wealth and worldliness in the Church (which at that time in England was uniquely Catholic) and he attacked both monastic life and the papacy. Thus, in every way he appears a forerunner of Martin Luther, except that he wasn’t as well-known or successful as his German counterpart (had you heard of him before now?) He eventually died of a sudden stroke, though his body was posthumously dug up and burned by Church authorities in 1428.

You might wonder why I, a very non-dissenting Catholic priest, like to come to this spot. The answer is certainly firstly for its natural beauty. But the second reason is to drink in something of that mix of fear and defiance which must have gripped these religious rebels as they stood confined by these damp and narrow walls hidden high up in the Peaks. What was actually going on here?

Simplistic analyses are not helpful in these cases. A black and white reading—with no real knowledge of the historical period—of Wycliffe’s life as a tale of a brave rebel fighting a corrupt institutional Church would do no service to the truth. No doubt there were faults on both sides. For all his valid points, Wycliffe was very extreme in a number of his positions and appears to have been used by the powerful nobleman John of Gaunt as an unwitting tool in the latter’s self-interested fight against Church authorities.

Nor we can we necessarily call this a period of religious decline with, therefore, Wycliffe as the unique luminary. Indeed, it was in many ways one of fervor in the Catholic Church. Great spiritual figures like Julian of Norwich, an Englishwoman despite her name; the mystic and Church reformer St. Catherine of Siena; and the now-classic writer Thomas a Kempis, were all on the planet at around the same time as Wycliffe, as was his fellow rebel in Bohemia, Jan Hus, who largely followed Wycliffe’s ideas. None of them were blind to problems within the Church but whereas the former three believed passionately in spiritual reform from within, the latter two favored more open opposition. Were these right for being so radical? Given what I am, you won’t be surprised to hear me suggest they might not have been, but I willingly recognize that they raised important questions and had these been answered in their time, the later split into Catholics and Protestants might never have happened.

But were our Lud’s Church Lollards heroes or villains, enlightened or dupes? We must have someone to accuse: either them or the authority which persecuted them. No doubt, there are numerous secret sects today which we would probably all agree are harmful to society and are best repressed—or “made illegal”, as we’d now put it (though most of us, I hope, would not favor burning their members, alive or dead, as the means to do so!) If you disagree with what I have just written, try substituting the word “sect” by “cult” and see if your opinion stays the same.

And as for the Lollards being “heretical”, what does it mean to be a “heretic” anyway? Today’s heretics are sometimes tomorrow’s heroes. When is a heretic a courageous revolutionary and when is he a blind and stubborn fanatic? Or he might be a bit of both. It’s also a striking thought (it strikes me at least) that whereas in the past a heretic was someone who denied specifically defined doctrines, a heretic today could simply be someone who stands against fashionable opinions. So I could be a heretic, a deviant from the “norm”, simply by upholding traditional moral values which have enjoyed universal acceptance for centuries but which no longer suit contemporary palates. A heretic in the past was someone opposed to what was considered objective truth. A heretic today is someone who dares to claim that objective truth might still exist and require our consent.

I come here to Lud’s Church to grapple with all these questions and to try to learn a bit of subtlety. Yes, to be challenged by “heresy”, the frequent daring of its proponents and the validity of many of their claims, but to learn also that there are usually two sides to every argument and the underdog is not necessarily the innocent victim. Might is most certainly not always right, but nor is it always wrong. Too easily we have a prejudice against “the institution”. I am perfectly prepared to believe that individual bishops could have dealt heavy-handily with this or similar situations (the Catholic Church can be as incompetent as any other organisation), but I will not condemn them simply for seeking to check the Lollards’ doctrines if they genuinely believed they represented a threat to the people under their charge and to society’s stability as they saw it. Yet it is also the case that while, as a Catholic priest, I believe in and seek to be deeply loyal to my Church, I have come to appreciate that we have a lot to learn from those who oppose it, also from within. They too may well have a valid point to make.

The place certainly speaks to me of fear more than faith. Were these Lollards theologically literate dissidents—I think, unlikely—or were they hoodwinked in their turn by somebody, perhaps the above-mentioned Walter de Lud-Auk, who wanted to enjoy religious authority over them? We will only find out in the next life. And yet, these clandestine worshippers were in their own way brave people who were ready to take significant risks for what they thought they believed in. I doubt that anybody went to Lud’s Church for earthly gain, and they probably had a lot to lose. So, questions abound and, in part, we travel to prompt ever further questions, constantly challenged by what we see and experience.

So, leaving open the question as to whether this really is a holy site or not, I think we should always be open to the possibility that places can be sacred. We can visit them to feel faith in the stones around us. For someone with religious sensitivity, spiritual grace can be touched in the very rocks.

Numerous fantastic stories have attached themselves to Lud’s Church. Some claim that it was used by Robin Hood and Bonnie Prince Charlie or was the site the anonymous author had in mind for the final showdown in the 14th Century poem “Sir Gawain and The Green Knight”. Today, there are not a few people who would see religion as just one more fantasy tale. But places like Lud’s Church call on us not to be so simplistic. First of all, some study is required to know the facts; how ignorant we can be of what we blithely disregard. Then one needs at least some sensitivity to sacred sites, which have spoken to many people throughout the centuries and surely not all of them were complete fools. And finally one must be ready to be challenged by the convictions of others, whatever you might believe—or not.

Suggested next reading: Discovering Beauty In Liverpool: A Gallery Definitely Worth Seeing