One must travel through space to travel through time. Only by going physically to a specific site can all the history encapsulated in that location reach us today.

These reflections are prompted by my recent visit to the shrine of Our Lady of Fernyhalgh, near Preston, in the county of Lancashire in North-West England. Tucked away in the midst of fields, one gets a sense of just how remote this place would have been in its day, though the constant whooshing—faint but audible—of the nearby motorway reminds one that, in Western Europe, it is almost impossible to escape modernity altogether.

To go to Lancashire is to go to a place abundantly blessed in its rugged and rolling hills and in the—still today—cheerfulness and warmth of its people, and this despite the dourness and decline of many of its towns. Though it lacks the majesty of the Lake District to its north and the Peak District to its east, it is still a charming county with charming scenery and folk. It might be “grim ‘oop North” on a rainy day, but the Lancastrians can usually laugh it off with a jolly chortle. And I like to think—but I am a Catholic priest, so assume I’m biased—that this cheerfulness has something to do with the region’s history of Catholic faith, first through many brave souls who stood firm in their beliefs in hard times and then through the Irish immigrants who flocked to the county in the 19th Century.

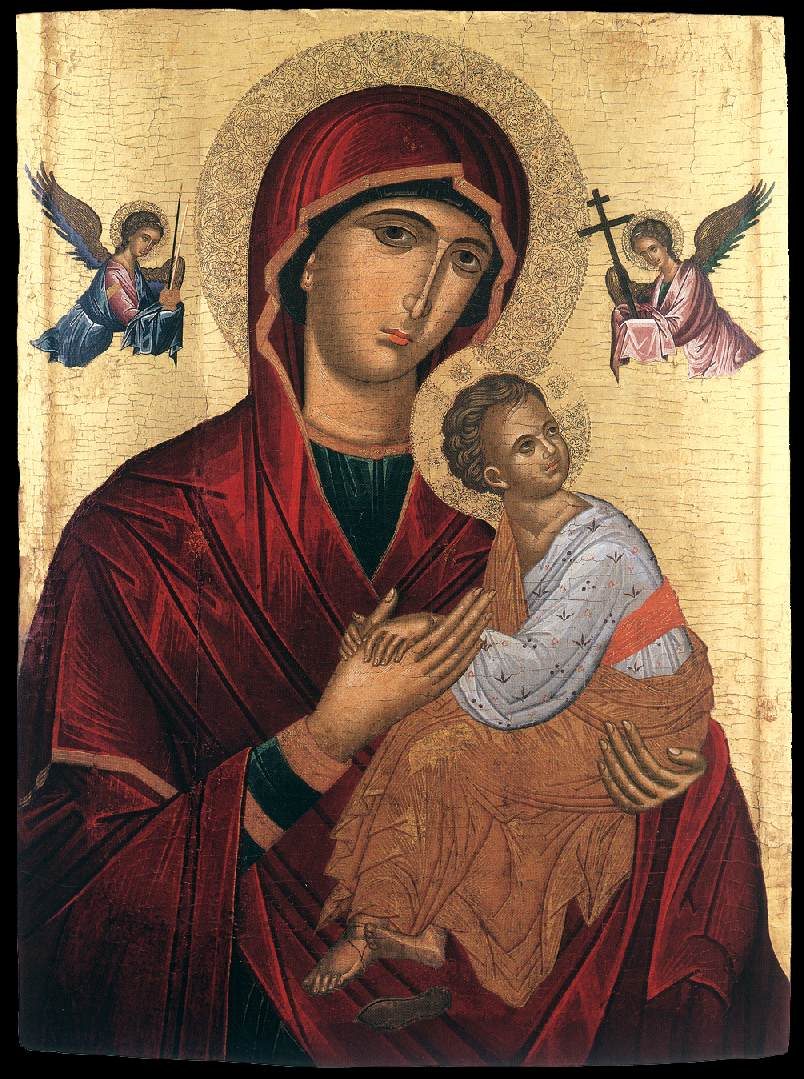

Fernyhalgh—also known as Ladyewell—is a witness to this fidelity. It is an ancient centre of devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, much loved by Catholics in these northern climes. If Lud’s Church spoke to me of fear, defiance and dissent (which, as I wrote in my previous post, also have positive sides to them), Fernyhalgh breathes a different atmosphere. One can still sense in its tranquil serenity something of the faith and courage of those Lancastrian Catholics who continued to go to pray at the shrine even in the worst years of persecution in the 16th and 17th Centuries. Bear in mind that at this time Catholics risked being hung, drawn and quartered (only look up what this means if you are not squeamish) for celebrating Mass (if priests) or staying loyal to the Pope and Church of Rome. To go to Ladyewell was, therefore, to risk being fined, imprisoned and even potentially killed. But go they did. All for the love of a woman, Mary, the Mother of God, as Catholics revere her.

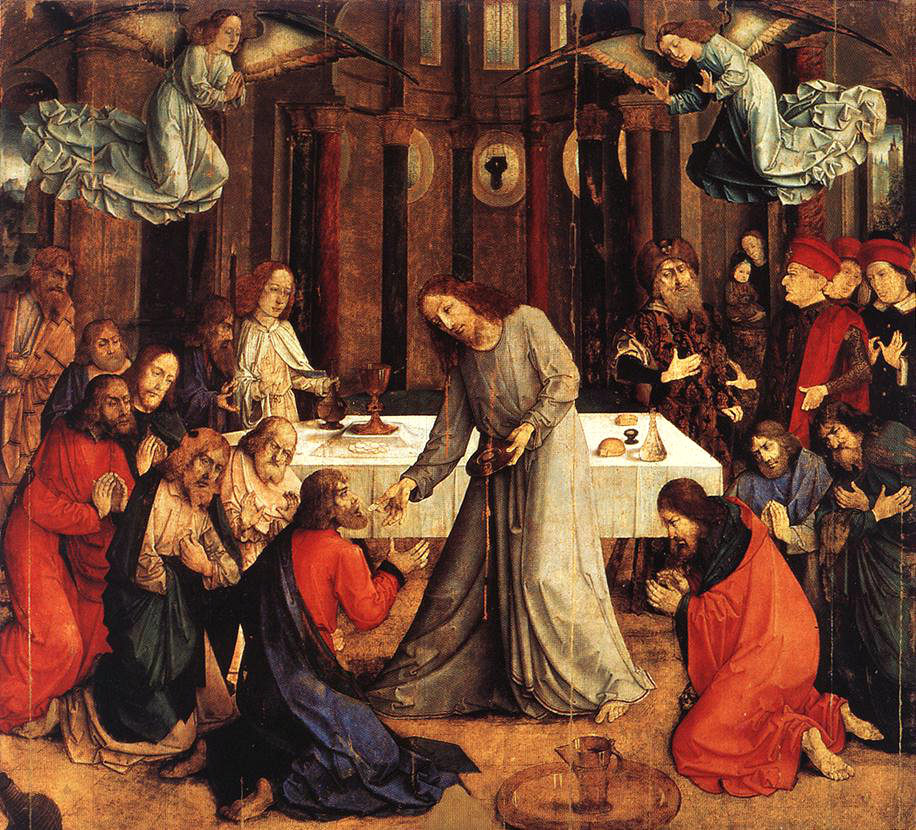

What is amazing about the faith of these people was their devotion to a rite which many modern Catholics find boring and invent all sorts of excuses to avoid: I mean the Mass. This Catholic sacrament had been outlawed by the government and replaced by a new Communion rite based on a more Protestant theology. But many Catholics were determined to keep attending it and did so in secret sites up and down the land. Numerous country houses, run then by Catholic gentry, bear witness to this, with the hidden chapels and hiding holes for priests in case of a raid by government agents. Scores of young men went abroad to train for the priesthood and returned in disguise to minister to the clandestine Catholics, knowing it was only a question of time before they would be arrested and executed. Ordinary lay people—men and women, like St Margaret Clitherow, a butcher’s wife in York—risked and finally gave their lives to hide these priests. All for love of the Mass. Fernyhalgh has numerous relics of these martyrs.

Of course, if one really believed what the Mass is, one would not be surprised at this. For us Catholics the Mass is the re-living, the making present each day, of Jesus’ death on the Cross and his rising from the dead. When, at the Last Supper, he showed bread and wine and said “this is my body which is given for you” and “this is my blood of the covenant which is poured out for many”, and added “Do this in memory of me”, he was instituting the Mass. The Mass makes present Jesus’ giving and pouring out of his body and blood on Calvary Hill, anticipated in that supper and then re-enacted through this sacrament. If you truly believe that this is God in human form offering his life and whole self to you, then risking your life for him is no longer such a big thing.

I appreciate that all I have said thus far could appear to some readers as a form of Catholic triumphalism, basking in the glory of these illustrious past co-religionists. While I think that anyone who actually checked the facts of what I have written would find them to be correct, I certainly sympathize with this concern in that it is also true that we should never travel to blame others. To travel to fuel prejudice is almost the antithesis of the purpose of traveling. To travel is to open one’s mind, not to close it. While it is perfectly valid to travel in order to grow in faith—which is precisely the point of that particular genre of traveling we call “pilgrimage”—we should remember that faith must never become fanaticism. It should be a journey to a new place, not a return to old grievances. A pilgrimage should aim at the conversion of heart, not its hardening.

And so while I go to Fernyhalgh to be inspired by the bravery of these ancestors in religion—to try to live my faith today with the same courage they showed then—I also realize that I must not go to nurture a grudge or a victim complex. Besides, I am fully aware—to my shame—that while many Catholics have suffered great brutality in history, not a few have inflicted it on others. Thus, living faith should never be fostering resentment. As much as one might have suffered, collectively or even personally, the only way forward is to seek one’s own conversion, and not spend one’s life expecting others to say sorry. If we turn to God and virtue ourselves, others might in time follow our example. This “turning” is why we go on pilgrimage.

So, let me finish these reflections with some words from an ancient Christian writing attributed to a certain St Dorotheus. Put simply, the text’s advice is: blame yourself, not others, a self-blaming which, I would add, is an absolutely essential way forward in any ecumenical or inter-religious dialogue. In what way do I need to change to overcome the pride, greed, insecurity, bitter zeal or narrow rigidity which might lead me to mistreat others, in the name of religion or any other apparently noble cause?

But let the text speak for itself: “The reason for all disturbance, if we look to its roots, is that no one finds fault with himself. This is the reason why we become angry and upset, why we sometimes have no peace in our soul … We hope or even believe that we are on the right path even when we are irritated by everything and cannot bear to accept any blame ourselves. This is the way things are. However many virtues a man may have … if he has left the path of self-accusation he will never have peace: he will be afflicted by others or he will be an affliction to them, and all his efforts will be wasted.”

Suggested next reading: Questions You Need To Ask Yourself Before Traveling